The origin of the word “romantic” is in roman, an Old French word meaning, simply “something written in the popular language” (Columbia Dictionary). In the Middle Ages, it referred to everything from the narrative Poema del mio Cid to the Breton/Cornish stories of Tristan & Iseult and the French chansons de geste of Roland and Roncevalles. The word was debased by its association with an 18th/19th century literary/artistic (and later musical) movement which built from the archetype of Goethe’s seminal Faust, and the intoxicating empirical method of the Enlightenment, to sculpt a model of artistic creativity which fetishized individuality, autobiography, and the Hero’s iconoclastic journey. It led to a lot of great music with contemptible or egocentric, and often remarkably bourgeois programmatic motives (see Berlioz, Wagner, Schumann, Richard Strauss, et al).

But originally, despite the way it was later appropriated by higher classes as “art,” in the medieval vernacular, roman simply meant tell me a story. And a story that could build from well-loved archetypes (see Joseph Campbell’s seminal The Masks of God), particularly one which understood that human beings have a visceral desire to try to make sense of the joy and the tragedy of existence, accrued all the additional power of instinctive familiarity. So a popular artform, in a vernacular language, that built upon archetypes to tell a story of joy and of loss, could be a pretty fuckin’ powerful artform. And music that could do the same could be similarly powerful.

This was the great insight of nineteenth-century music: that instrumental music could have both an experiential/emotional and a narrative force, and that the two could be synthesized to create powerful musical storytelling: of the pastoral (Beethoven Six), the defiant (Beethoven Five), or of sorrow and acceptance (Mahler's Lied von der Erde). It’s also the insight that drove the invention of opera, a genre responsible for some of the greatest achievements (Monteverdi’s Orfeo, Mozart’s Don Giovanni, and Stravinsky’s Rake’s Progress) and most beautiful yet banal self-indulgences (say, for example, most of Strauss’s oeuvre) in the history of Western “art” music. Musical narrative is powerful.

Though I diss the 19th-century Romantics, it’s not because I think the music is bad. In fact, the music is great—it’s just that, in some of its most beautiful manifestations, it’s too often tied to this dumb-ass, bizarrely mundane and middle-class philosophy of gimcrack “heroism.” That egocentric self-obsession, which reached its apotheosis in the “total arts works” of that great composer (and “bit of a crook,” to quote Robertson Davies) Richard Wagner, and which Mahler was both too smart and too much of a Viennese outsider to buy-into unqualifiedly, was what Debussy, Stravinsky, and the underrated and misunderstood genius Erik Satie (whose Parade is the subject of an upcoming “100 Greats” post) were all reacting against.

At the end of the nineteenth century, with its long-overdue dismantlement, which had been led by the French impressionists, the Italian Futurists, and the general realization (so obvious that even composers, a notoriously cosseted, out-of-touch, and politically-naïve bunch could see it) that Things—empires, economic systems, artistic philosophies, "civilized" war—were ending, the Romantic narrative impulse in orchestral music moved out of the concert hall. Assaulted by the intentional “barbarians-over-the-walls” ethos of Primitivism (Le Sacre du printemps, Bartok’s Allegro barbaro, and Ellington’s “jungle music” being three exemplars), the simple-minded proto-Fascist utopianism of the Italian Futurists (Marinetti, Russolo, later Varese), and the charge of “anything but those damned Germans” nationalists from all around the circumference of Europe (everyone from Bartok and Stravinsky, again, to Vaughan Williams, De Falla, Sibelius, Ives, and on and on), conventional orchestral Romanticism was largely banished from the new-music concert hall. And not before time, in my opinion.But, one place that the neo-Romantic narrative instrumental impulse went was the most logical, yet critically undervalued, place in the world: to the arenas of live music for cinema, and, eventually, the film soundtrack.

The late ‘20s were a fantastic time in the history of film music, because the most traditional, conventional, “popular”, and “experimental” musics were all jostling one another for space in the “moving-picture halls” (mostly, converted vaudeville theatres). Chaplin wrote music for his own silent classics, organists and pianists all over North America improvised from a grab-bag of late-19th-century light classics, in Northern Ireland the great traditional fiddler Neillidh Boyle was renowned for the train imitations he improvised to Edison shorts projected on the walls of Donegal barns, and a whole generation of Central and Eastern European composers, trained in the salons and conservatories of Vienna, Berlin, and Paris, fled Europe's Great Depression and the rise of fascist governments to come to America, where many of them found work on the recording stages of the great Hollywood orchestras. This is how, and where, and when, late-Romantic musical narrative techniques were adapted to realize the mature and eventually predominant form of movie music.

And that makes perfect sense: late 19th-century orchestral techniques had used quotation, allusion, and imitation so extensively to tell Romantic and nationalist “hero-tales” on the concert stages of Mittel-Europ that those techniques had become their own semiotic language: strings for pathos, brass fanfares for heroism, march rhythms for martial valor, synthetic and minor modes for “exotica,” and so on. It was a language that early cinema audiences recognized and it helped to tell the story in those classic Hollywood films (a separate tale, for another day, is that of the fantastic but ultimately marginalized experiments with avant-garde music and Dadaist, Surrealist, or Expressionist film). In film music, the egocentric autobiographical focus of the late-19th-century (typically German) tone poem was shifted, to the more modest, more accurately “romantic,” and more legitimately profound goal of telling the fuckin’ story.

I first encountered the fantastic Michel Legrand and (uncredited) David Munrow soundtrack collaboration for Richard Lester’s The Three Musketeers at the age of 15, in the summer of 1974, on a visit to England and Scotland. It was the first time I ever traveled overseas, the first time I ever traveled long distances without parental supervision, the first time I’d ever been to Britain. I traveled with my friend Larry, my oldest (literally: we met in kindergarten) musical friend, and I learned a lot about traveling, about relating to people, and about the stresses that the combination of those two activities can bring to bear, especially on two out-of-their-element 15-year-old adolescent males: we almost came to blows in our Edinburgh youth hostel. But in the event: we chose not to swing at each other: we got over it, and we learned that a friendship can survive and even be strengthened.

We traveled by 3rd class rail—this usually meant standing up: I still remember the ride from Edinburgh to Manchester, standing on the jostling open platform between carriages, playing fiddle/harmonica duets. We drove through the Lake District, magnificent views and precipitous 1-in-3 grades, in a right-hand-drive Ford Capri, white-knuckled as the driver swerved from one side of the narrow macadam roads to the other. We rode a bus to the shores of Loch Ness, we saw a ghoul in a little churchyard at Great Budworth in Cheshire (since corroborated by independent observers) and we were taken for 30 quid apiece by a con-man in Trafalgar Square.

I had the first (and still the hottest) curry I’ve ever had—to this day, in a curry house, I know to say “Hot—but not London hot!” I saw the only film ever made from George MacDonald Fraser’s fantastic “Flashman” series, and read the first of the books in that series (a literary encounter that would transform my sense of what the craft of history could accomplish), and the Young Vic’s revival production of Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead, in London on that same trip. And I saw Lester's The Three Musketeers.

So to my experience of this film and its score. It’s an astonishing, seemingly-chance concatenation of fantastically compatible, highly idiosyncratic artistic talents: not only Legrand, who’s probably better-known for the score to The Umbrellas of Cherbourg, plus hundreds of Hollywood films, rather than this British/Spanish production; but also Richard Lester, who directed the great A Hard Day’s Night and the more-successful but less-funny Help! for the Beatles, and who never attained to the same heights of genius as in the Musketeers films; George McDonald Fraser, author of the “Flashman” series, but the mood and character of whose screenplay, when matched with Lester’s comic Altman-esque pratfalls and cross-conversations, is still a textbook example of how “old” Hollywood could combine both fantastic story-telling and credible historical accuracy.

The casting is coincidentally impeccable: the ageless Michael York, then in his 30s but utterly believable as the rube-from-the-sticks youngster hero D’Artagnan; the great Frank Finley, creating a wonderfully apposite and over-the-top version of the speechifying blowhard Porthos; pretty Richard Chamberlain as Aramis the priestly lady’s man. And Oliver Reed playing the role he was born to play, the brooding, frightening tragic hero Athos. Reed had been magnificent—dark, terrifying, and charismatic—as Bill Sikes in the 1968 film musical Oliver (which had also featured Jack Dawkins (RIP) as the Artful Dodger, Ron Moody as Fagin, and Shari Wallace’s heartbreaking Nancy), but his Athos, the nom de tragedie of the aptly-named Comte de la Fére, caught the ferocity, nobility, and sorrow at the heart of the character: as Dharmonia said, it didn’t matter how youthful York looked, or how decorative Chamberlain was—Reed was the one who made the women squirm. It’s also one of the best and most extensive roles for Raquel Welch, spectacular chest well to the fore, as a surprisingly effective Constance, love interest of York’s D’Artagnan (though this is the one place in which the movie is a bit mean-spirited, portraying Welch’s beauty as a ditz prone to pratfalls and confusion).

The cast of villains is equally great, equally resonant of the layers of cinematic associations which the individual actors would have evoked: the great Christopher Lee as the meticulous assassin Rochefort; perhaps the only good acting job Charlton Heston ever did, his shockingly persuasive, ironic, suave, and patrician Cardinal Richelieu; Fay Dunaway as the heartless murderers Madame de Winter (looking as perfect, and as cold, as a porcelain miniature—or perhaps an enameled dagger).

It’s a marvelously comic film, which in fact is better than the book upon which it is based (same holds true, for example, of Coppola’s Godfathers I & II): Dumas' Mousquetaires was published in the 1840s, when Schubert was already dead, Berlioz had descended from the heights of the Sinfonie fantastique and was devolving into a mean-spirited middle-aged newspaper critic, and Paris still believed in the bullshit charlatanism of Romantic egocentricity. But the film takes off from the great story told in the book, and builds backward toward an historical awareness of how people might dressed, talked, fought, eaten, farted, worked, loved, and died in the 17th century. As a story, it owes a lot more to the folk-tales and war-stories upon which Dumas drew, to the psychological acuity of contemporaneous Altman, and to the wisecracking period humor of the (deceptively accurate) Monty Python and the Holy Grail.

In addition to the very credible comedy of the leads, it also features the talents of the great Shakespearian buffoon Roy Kinnear as the Sancho-Panza-esque Planchet, and the inimitable loony genius—channeling at least 7 centuries of Punch-and-Judy cuckolds—Spike Milligan as Constance’s craven husband Bonacieux.

The serendipity continued behind the scenes: crew include the great fight director William Hobbs, who also did the masterful comic combat sequences in Shakespeare in Love , Depardieu’s Cyrano de Bergerac, Ladyhawke, Royal Flash (another Lester/Fraser/Oliver Reed collaboration), and the definitive edged-weapon film The Duellists—the only film able to give The Seven Samurai and the later The Two Towers a run for their money, and one of the few films I’ll still watch by Ridley Scott, whose pathetic sub-Victor-David-Hansonian historical revisionism betrayed the real nobility, courage, and self-sacrifice in the True Story of Black Hawk Down in favor of cheap triumphalism.

For Three Musketeers, Hobbs’s fight sequences manage the difficult filmic task of being both wonderfully visual and viscerally plausible. The actors did almost all their own swordplay, and there were multiple contusions, concussions, and broken bones, and watching it, you believed it, particularly Finley's flowery pratfalls, York's yokel agility, and Reed's looming ferocity—I’m sure this same lot would never risk their Hollywood hides like that again. That serendipity also involved some truly bizarre random notes, as well: the sailing sequences were coordinated by Dublin-born Mike Hoare, the notorious ex-mercenary “Mad Mike” who had led paid soldiers in the African colonial wars of Katanga, the Congo, and Biafra (and 4 years after this, was behind the absurd attempt to led an armed rebellion in the Seychelles Islands. Of all places)—London in the early ‘70s was a very strange place.

But really, the unsung hero of this soundtrack is the brilliant, tragic genius David Munrow, who helped found London's modern revival of historical winds-playing, wrote one of the earliest and still one of the best books on historical organology (Instruments of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance), collaborated with British folkies like the Young Tradition and Shirley Collins, hosted series on the BBC, and released more than fifty LP’s of historical repertoire, as well as supplying period music for this film—and who took his own life just two years later.

Between them, Legrand and Munrow present a textbook example of the expressive and narrative capacities of film music, drawing on both old-school Hollywood and new-school historical performance in service of telling the story.

The LP is long out of print and has not (I don’t believe) ever been released on CD, but it can be heard on the excellent DVD reissue of the two films, and Legrand has released a short orchestral suite based on just a few of the key themes:

The magnificent, pounding minor-key fanfare for low winds and strings and which serves as underscore for the opening credits, a wonderful back-lit sequence catching swordsmen (later revealed to be D’Artagnan and his father, sparring) in slow-motion silhouette as they thrust, parry, and riposte, and which beautifully prefigures the life-and-death staggering, brutal fatalism of the decades-long combat in 1977's The Duellists;

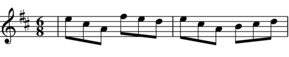

The beautiful recurrent 2/4 allegro theme for high winds, celeste, and strings, which simultaneously tropes all those heroic sequences in earlier Hollywood films, but also whose rhythms and modal inflections manage to evoke both the pounding of horses’ feet and the drone-based folk-music textures of the French rigaudon;

The great call-and-response theme, for high winds versus running strings, and underscored by kettledrums, that accompanied battle scenes, with a lyric secondary theme;

Equally wonderful, though lacking from the suite, and sadly and criminally uncredited on the original film, are the wonderful, grainy, funky cues and other bits of miscellaneous entra’acte music which David Munrow’s wind players supplied: to scenes of markets, nuns hanging laundry, dyers coloring cloth (and serving as unwilling witnesses to a great, slapstick combat between Musketeers and Cardinals’ Guards, most of whom wind up doused in indigo or red before the end), and all the other scenes that served not just to advance the story, but rather to convey the feel, the sound, and even the smell of 17th century France. Munrow knew what the period sounded like, and he made me know too: in hindsight, this might be the earliest extensive listening to historical instruments I’d ever encountered.

This is another of the records I discovered amongst the racks of battered and worn LP’s in my home town library’s media collection, a place I visited religiously between the ages of about 10 and 16. I found this disc (along with the great National Geographic’s Songs and Sounds of the Sea), just after getting back from England, and I am quite sure that, if were still there, the old blue-lined “Borrowers” index card would still show my signature occurring more frequently than any other.

I had never sat down and listened to film music, and I had not really noticed the music in the experience of watching the film in London, but as I played that battered LP, which I came to know so well that I could even tell when and where the nicks, scratches, and skips would occur (and could anticipate where to jog the tone-arm ahead to minimize those latter), I began to get a grasp of the narrative capacities of instrumental music. It wasn’t just that I had loved the film (hell, at age 15, I wanted to be Reed-as-Athos, and cultivated a generally-unsuccessful aura of brooding tragedy), or that I could associate the specific musical cues with scenes I had enjoyed.

It was more that the Legrand/Munrow score demonstrated to me, in the most immediate, intuitive, and visceral way possible, that instrumental music, especially if allied with words, could both tell a story and evoke much more complex, individual and transformative emotional responses to that story than could the words or actions alone. And, that the music of a period could be as evocative of that period as any other cultural expression.

It’s an old, old realization, of course, and, although the Romantics got confused and lost their way in the tangled self-referential thickets of Individualist egocentric autobiography, the insight goes back in the Western tradition, past Strauss and Wagner, to Weber, to Mozart, to Gluck, to Monteverdi, but even further: to the Mystery Plays of York and Cheshire, to the liturgical dramas of Hildegard von Bingen, to the troubadors and trouveres of France and the anonymous Jewish, Christian, and Muslim poet-musicians who assembled the Cantigas de Santa Maria, to the very foundations of the Latin Mass itself.

It’s the power of the word, the music, and the story, together, to express the deepest, most intuitive, most archetypal aspects of human experience: joy and loss.

This post is offered in memory of the much-missed David Munrow (1942-76), and dedicated to my brother-in-music Larry Young: my oldest and still one of my best musical friends, with whom I embarked on many journeys, and with whom I learned an awful lot, awfully early, about being a musician and being a man.