I don't know when I first developed a strong propensity for sitting in public places with my back to a wall: could have been my time as a barroom doorman, or some of the bars I played, or even just reach back to my early-adolescent self-dramatization. At any rate and for whatever reason, and as Dharmonia can attest, I get a little woodgy sitting in a pub or restaurant--or party or concert, for that matter--with my back to the room.

But I don't think it's just self-dramatization...because I've been prioritizing sitting in the corner to play music--usually acoustic music--almost as long as I've been playing music, and that's almost forty years. I learned, close to four decades ago, that the corner of a performance space was a powerful place: not just for what it provided for vision or vantage--the ability to see the entire space and the interactions of pretty much everyone within it within a 90-degree arc--but also because of the acoustic AND semiotic energy that it focused.

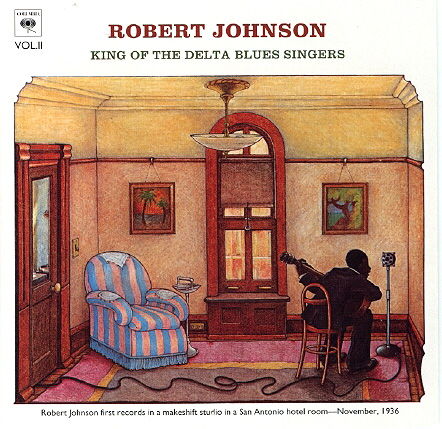

There's a beautiful, iconic oil painting which was used for the 1970s reissue of the Robert Johnson blues 78s from the late 1930s; at that time, none of us had ever seen the beautiful couple of posed photos that are the authenticated portraits of Johnson. The image also picks up on a story that was told by the great recording engineer H. C. Speir about Robert's first sessions in a San Antonio hotel room in 1936--a story that was picked up again in Walter Hill's flawed but evocative Crossroads: Speir told the story that, at that first iconic session, Robert was so nervous that he refused to face the microphone. Instead, he dragged a chair across the room and insisted on playing facing the corner. The way they told the story in the '70s, it was "evidence" of Robert's "tortured shyness" and hence, in the cut-rate Romanticism that blues heads still tried to find in their (preferably deceased and therefore speechless) heroes, of his "greatness."

The image also picks up on a story that was told by the great recording engineer H. C. Speir about Robert's first sessions in a San Antonio hotel room in 1936--a story that was picked up again in Walter Hill's flawed but evocative Crossroads: Speir told the story that, at that first iconic session, Robert was so nervous that he refused to face the microphone. Instead, he dragged a chair across the room and insisted on playing facing the corner. The way they told the story in the '70s, it was "evidence" of Robert's "tortured shyness" and hence, in the cut-rate Romanticism that blues heads still tried to find in their (preferably deceased and therefore speechless) heroes, of his "greatness."

In fact, as Ry Cooder, music consultant (and guitar soloist) for Hill's film, made clear, it was nothing of the sort: it was evidence of Robert's precise, imaginative, and expert manipulation of available artistic resources. As Elijah Wald argued in his great Escaping the Delta, Robert was anything but "primitive." Though only a generation separated him (born in 1911) from the great Charlie Patton (born in 1891, and the real "King of the Delta Blues"), Robert was infinitely more aware of the big world out there, up to and including the medium of "electrical recording," which was already--by '36--drastically transforming blues singers' sense of their own horizons. Patton played for booze and smokes and fish sandwiches--and for the women who usually wound up supporting him--but Robert, who was probably playing electric guitar, with a full rhythm section, before he died in '38, was carefully crafting an approach to songs and arrangements that was intimately aware of the restrictions, and the possibilities, of the 78-rpm record.

What Robert understood, in his very first recording session, was that facing into a corner would "load" the bass frequencies--compressing, concentrating, and amplifying the sound of his Stella guitar--so that much more of the performance's dynamic range would come out: the complexity of the arrangements, the subtlety of the slide work, and so on. The result was that the records sounded different than almost any previous solo blues performances.

Well, corner-loading works pretty well--and not only for recording. Pretty much every session I've ever led--by chance, intent, request, or coincidence--I've tried to get myself stuck into the corner with my back to the wall. Aside from assuaging my sub-"Aces & Eights" paranoia, sitting in the corner usually means that the sound is a little better focused, that other players can hear me a little better, and that--maybe least obviously but most significantly of all--I can see what's happening.

Sure, there's the simple geometry of facing outward from the intersection of a 90 degree right angle: 1/4 of the horizon, pretty easy to see everything across and around the room. With the players facing inward toward one another in the circle, we can all hear each other.

But it also lets me see beyond the players, and listen past the sound, to what else is going on around the room. When leading a session, I can't move around too much--though I will put down the instrument while the other players continue, and "work the room" like a politician, saying hello, making introductions, hunting chairs for people, and so forth--but even while playing, I can observe what's happening. And only about 1/2 my attention is on the music--and on a good night, it's even less than that.

Instead, and beyond, what I'm paying attention to is the various markers, visual and otherwise, that tend to reveal the social dynamics of the experience that everyone present is having: who's talking? who's listening? which asshole just waltzed into a room where no other person is smoking and fired up his ostentatiously-cool American Spirit cigarette? Is it time to climb on a table right over that asshole and turn the ceiling fan on High? Who's buying drinks for whom? How many are familiar faces? Which ones, of those we know, look like they need a little help or some attention? Who's unfamiliar? Who looks like they just wandered in by chance, and how is that person reacting? Is s/he looking around bewildered, or just happily surprised?

I think about this shit constantly during a session, and even more when the music is going really well and I can split my attention to other things. Because I think the music can heal people. Because I actually think it's possible to pick the right tune at the right moment and make life better for every single person present--at least for that 3:00 minutes--if I'm paying close enough attention and making the right choices based on that moment-by-moment attention.

I believe the music can do that.

This poem has been on my office door since Sept 12 2001:

"Music happens inside you. It moves the things that are there from place to place. It can make them fly. It can bring you the past. It can bring you the things that you do not know. It can bring you into the moment that is happening. It can bring you a cure."I believe it about the classroom, too.Timothy O' Grady (I Could Read The Sky).

2 comments:

You just blew my mind:

Robert Johnson, on an electric, with a full rhythm section...

You hear that? Yup, that fizzing sound is what's left of my brains!

Also, that American Spirits guy sounds vaguely familiar. Hey! is you talkin' 'bout me?! Hahaha.

Yep. I suspect it sounded a whole lot like Robert Jr Lockwood and Sonny Boy II in Memphis, right around the same time. Funky as hell, for sure.

Post a Comment