Just too little time today. Working on a few things.

In the meantime, GOTV!

Thursday, October 30, 2008

Placeholder edition

Posted by

CJS

at

8:58 PM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Wednesday, October 29, 2008

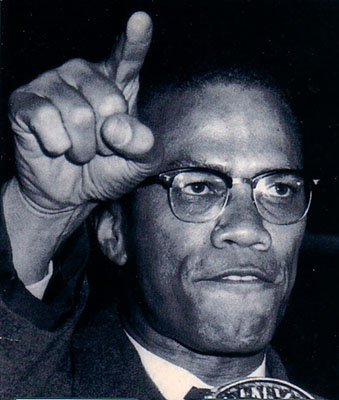

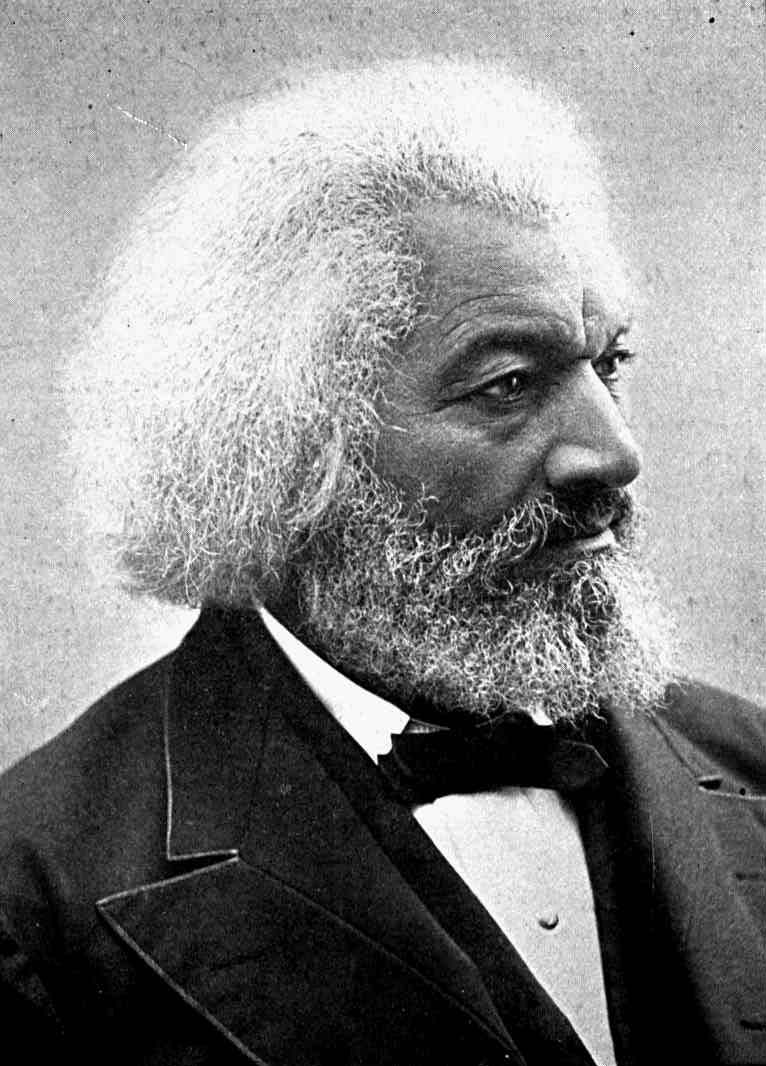

The Black President

That, my friends, is a Leader. We'd almost forgotten what it felt like, hadn't we?

I don't know if he'll live up to any of these. But I think he has the capacity to stand in their company.

![[F15.gif]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiw3VNMr-ZbR72yIMZYk4bqYyH0q3pm9HOMCpgPlpKcYIzs_qB5uT-JG3gjX7SYzh0h0eMgLMrgn_jKrWVfjzZrOTFz4sOwlLENxAuCvKcksyLXO3GTEXhNc90jtORigg-h5T-Vhw/s1600/F15.gif)

Posted by

CJS

at

6:30 PM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: radical politics

Tuesday, October 28, 2008

"The Office" (workstation series) 114 (home-again-home-again edition)

Rainy cold day in central Connecticut, the kind that you know made the 17th-century Dutch and English Wesleyites who settled here on either side of the Connecticut River feel right at home. I’m from points north of here, but this terrain of hardwoods and granite bluffs and little brooks is very very familiar—particularly at this season of the year, when the scarlet maples and golden elms tear at my heart.

Rainy cold day in central Connecticut, the kind that you know made the 17th-century Dutch and English Wesleyites who settled here on either side of the Connecticut River feel right at home. I’m from points north of here, but this terrain of hardwoods and granite bluffs and little brooks is very very familiar—particularly at this season of the year, when the scarlet maples and golden elms tear at my heart.

Up on out of here in a little while; right now, courtesy of tripadvisor.com, it’s breakfast at O'Rourke's Diner in Middletown. In the image: about 400 calories more, on one plate, than I need to eat in a whole day. But how often are you going to find a righteous Irish fry, cooked by an Irishman, in West-by-God-Texas? Going to need to spend the day either herding cows up- and down-hill, or eating watercress—no middle way.

O’Rourke’s is on the wrong end of town, right next to the dilapidated storefront Apostolic Baptist Church ("all denominations, all faiths welcome”), next to the spillway that runs down to the river from the town’s old mill. The menu has FIVE PAGES of breakfasts; it’s the kind of place where the locals have been going for the past 40 years, in whatever location Brian put the place. A perpetual winner of area diner competitions, it’s in the classic old-school railroad car design, but thankfully free of the faux-50s kitsch of the "Route 66 Remembered" places I know from the Southwest.

Counter is anchored by the old guys who've been coming to whichever was the current location their whole lives, and in each of which places have figured out which corner eave just outside the door provides most protection from the weather when they step outside to suck down the Kool or Marlboro that "those bastards down the state house" have now made illegal inside.

Old-school diner waitresses, who know everybody's order, wear sneakers for comfort and black clothes to avoid showing spills, aren't afraid of anybody (and treat the neighborhood street people who come in with great, if brusque, kindness and compassion, and make sure they get some toast 'n' jelly and a cup of coffee before they leave), and whose accents, based in whatever part of the new immigrant world they come from (Palestine, Poland, Eritrea, or Laos) are overlaid with an endearing patina of central Connecticut honk.

The food isn't haute-cuisine, but if you grew up in this part of the world, then it, like the topography and the weather, is damned familiar. Cooks, either younger or older, who I recognize, who you know have been getting up at 4am for so long they don't even have to hear the alarm anymore. I can say as an old kitchen-rat myself that when you've been cooking a certain menu long enough, you don't even really have to think anymore: the order comes in (in this place, old-school as well: on a slip of mimeograph paper over a high aluminum pass-through), you read it, and then your brain pretty much shuts off: the eggs and toast or omelet and bacon or hash and home-fries or biscuits and gravy get made without much intervention of the thought process.

Not unlike my experience yesterday, presenting at the conference. When you've been doing this for awhile--when you've internalized the process and dynamics and basic physiological template of the 20-minute conference paper—you've learned reasonably well how to provide a certain basic value-for-dollar: you know how to create something that will be entertaining, engaging, with peaks and values in an effective flow, creating a nice change-up from the more droning pedantry which too many of us seniors or the nervous hyperactivity the juniors are prone to. It's in the same basic neighborhood as the razzle-dazzle that a competent classroom lecturer provides: necessary in order to keep a room of 100 wiggly 18-year-olds sufficiently engaged.

What that doesn’t always tell you is whether/how much the content of your presentation has value. When you’ve been working a given topic, say in this case the minstrelsy project, as long as I have, and have presented one-or-another version of the material so many times to so many diverse audiences, you can’t always judge the significance of that material. Any scholar who’s worked a topic long enough will know enough about that topic that his/her ability to assess its interest to anybody else will be substantially eroded. I can’t tell whether this stuff is of interest to anybody else—hell, I can’t even tell whether it’s relevant to any other scholarship.

In a case like this, you basically say, “well, I’m going to go on the basis of the template and tempo that has worked best for me with other topics in other circumstances” and hope that your earlier instincts about the material (going back, now, nearly 10 years for this project) were accurate. At the very least, one’s own sense of what I called in the Q&A period “messianic dedication” to the topic can translate as persuasive and engrossing, even for people not knowledgeable about the topic.

What this sometimes leads to, in turn, is a kind of “instinctive auto-pilot” in a presentation. If you’ve done it enough times, and you do it regularly (say, in the large-enrollment undergrad classroom), and you have really good command of your material, be it lecture or conference presentation or musical repertoire, then, like the short-order cooks at the diner, you don’t really have to think too much during the presentation itself. In fact—and I learned this first in memorizing and learning to present large amounts of oral-tradition material: long narrative songs or storytelling pieces—the best performances sometimes emerge from a space of “suspended” attention, where you’re not really making conscious or sequential choices—you’re just “hearing” the next thing in the material, while also clued-in on the body- and facial-language that every audience supplies or withholds, and juggling the pre-composed material with stream-of-subconscious interpolations of improvised material.

It’s a hard thing to describe—easier, just as with the jump-shot that I so often use as a metaphor for this state, to learn to recognize and then replicate. You shoot 10,000 jump-shots, paying attention to how they feel in your body as and after the ball leaves your hand, and then along about the ten-thousandth-and-first, you hit nothing but net, and your body remembers what it felt like at the moment the ball left your hand, and you knew, before the ball ever dropped, that it was a swish (there’s a great replication of this in Bull Durham, when Tim Robbins’s psycho-but-freakishly-talented pitcher “Nook” Lalouche is told “Don’t think, just throw” and proceeds to hurl a picture-perfect and unhittable strike, at which he says to himself “God, that was beautiful! What the hell did I just do?!?”).

That’s sort of what the right kind of presentation, or lecture, or improvised performance, feels like. When it’s working right—for me, anyway—I’ll “wake up” at the end of the performance and say “Jesus, is it over? Did it work?” Happened to me recently during a performance when finally, after 8 years, my medieval band played my home university. Went into an improvisation on the Turkish lavta built for me by the great Samir Azar, and woke up about four minutes later with almost no recollection of what I’d played—just that I had to take us into Dharmonia’s vocal. I thought it had been good—but really had no certainty of that. After the concert, I said to my band-mates, “Guys, listen, sorry about that…I just kind of went away for a while.” And they were kind enough to rave about it. I still don’t know whether I would have liked what I played—but, the lesson here is that I’m not an accurate arbiter; more accurate (and more significant) is how it worked for the audience.

So with my presentation yesterday. I certainly have command of the material, and certainly retain the messianic conviction that it’s important stuff in my discipline, and certainly have another 100 minutes or so worth of material I could talk about—which is why I love Q&A periods, because it permits me to sneak in so much additional material I’ve had to cut for reasons of time in the presentation. But I really truly didn’t have any idea whether those things would transfer to the audience as relevant, useful, or even interesting.

In the event—and absent any hubris, which I’m convinced I’m un-entitled to—it was a more-or-less impressive moment: I was presenting third and last on a panel of very bright people, with topics very well suited to my own, for a good solid house of people who know and are engaged with the topics as well. I like going last (when #’s 1 and 2 are responsible about time limits), because then I don’t have to be shy about staying on top of time restraints—however much time is left in the session for Q&A, we’re not stealing it from anybody following.

And for whatever reason, the stuff all worked: the multimedia, the topic, the flow, the presentation language, suiting the presentation style to both the topic and the audience and making sure those three factors were calibrated to one another. One marker of an effective presentation is the presence or absence of questions in the aftermath, the call-and-response inherent in most good and satisfying performances. For whatever reason, this topic just caught fire, and there were questions after questions, and lines of people wanting to talk more, and requests for business cards, and that peculiar sensation (familiar no doubt to the point of ennui for celebrities, no doubt, but pretty unfamiliar to the rest of us plebians) that people are looking at you as somebody they aspire to be like, not so much in terms of persona, but very-most-definitely in terms of scholarly insight.

Now, I studied with people in my field who were and are Giants on the earth, and I know my relative insignificance compared to theirs. So there’s not much danger of a swelled head: I put myself up against the Dick Baumans and Peter Burkholders and Tom Binkleys and Tom Mathiesens and George Buelows and James Kellys and Gearoid O hAllmhurains and Suzy Fulkersons and Thomas Thompsons of the world, and my humility is well-entrenched. And I’ll usually bring their names into any conversation with somebody hero-worshiping me. Because I want to say “it’s not me—it’s not my skills or my history or my effort or my ‘brilliance’—it’s the greatness of my teachers flowing through me.”

I still believe that. But I’m grateful, occasionally, as I age and evolve, to become a more effective, more transparent, more invisible, persuasive conduit for their teachings.

Below the jump: this was the day:

Posted by

CJS

at

10:31 PM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: Workstation series

Sunday, October 26, 2008

Saturday, October 25, 2008

"The Office" (workstation series) 113 (satellite B edition)

ConferenceBlog02 – or, where Robert B Parker gets it wrong

ConferenceBlog02 – or, where Robert B Parker gets it wrong

Day 2. My own paper's past and I can remark upon the passing scene.

This is one damn beautiful hotel. According to the literature, St Louis's old Union Train Station, built in the flush of the Gilded Age in the 1890s, had essentially fallen into abandonment when the railroad system died after WWII (final nail in the coffin was Reagan's declining to even consider bailing out Amtrak in the '80s), and was only recovered as part of a huge, and ambitious, restoration and re-purposing project within the last 10 years. And it is gorgeous, even if it’s stuffed to the rafters with Shit to Buy.

I have to admit that I still admire scholars: even the geeky ones, even the arrogant ones, even the self-loving ones. Particularly when I’m stuck for three days in an enormous building stuffed to the rafters and very carefully thought-designed to promulgate impulse-buying. That’s really what a “mall” is—it’s not about finding the stuff you set out to locate, it’s about introducing you to a bunch of stuff—fresh fudge, Budweiser beer mugs, mocked-up street signs that cater to your own profession or alma mater—that it would never cross your mind to seek out, much less blow money upon, unless and until you find yourself in 10-12 square acres of space designed precisely to deny you any other kind of mental stimulus than that (very temporarily) provided by buying shit you don’t need.

Scholars traffic in different currency. Because whatever you say about them—they’re isolated, they’re arrogant, they’re un-obligated and un-accountable for the quantity or quality of their own work, all of which are unquestionably true—they don’t mostly care about amassing shit. Books, maybe; a house, maybe; a decent retirement plan, maybe (though most of the scholars/teachers I know would stay on teaching and researching virtually forever, if their employers and cognitive retention would permit)—but the markers of attainment—cars, second and third homes, 30-year-old Scotch, expensive prescription drug habits, whatever—which some people have to substitute for a sense of real accomplishment, scholars mostly don’t’ give a shit about. They can be as petty, spiteful, impractical, childish, and greedy as anybody else—but they’re mostly not very materialistic.

For years I’ve been a guilty-pleasures consumer of Robert B Parker’s detective novels starring the shamus “Spenser.” Started reading them with the first one, The Godwulf Manuscript, about the theft of an early English manuscript from a thinly-described Harvard library, and have continued since, buying them furtively and second-hand in used-book stores, and embarrassed to have them out on my shelves where the kids who house-sit for us can see them (in interesting contrast, I’m unashamed about the Robert E Howard “Conan” and C.S. Forester “Hornblower” novels, maybe because those latter are, in my mind, superb and unpretentious examples of respectable genre fiction—situations in which the author respects the genre and doesn’t coast in her/his efforts within it).

Parker is different—for years, now, he’s basically been writing slight screenplays in bound form, rotating his stock company of characters through telegraphically-short 1-dialogue-scene chapters and cranking them out for us to consume pretty much like potato chips. And with about as much lasting nutritional value.

I keep reading them because of (a) the Boston locations—Parker really does know the city; (b) the great (if simplistic and stereotypical) second-bananas, most notably the shaven-headed Big Scary Black Man assassin Hawk, played to perfection in the (deservedly) short-lived Robert Urich teleplay by the great Avery Brookes, years before he was Borged by the Star Trek franchise. But, they’ve gotten slighter and slighter—as Parker has more and more obviously coasted through low-effort recycling of past efforts, and as the blatancy with which he uses these thin fictions to redress or rewrite the ins-and-outs of his own life with himself as the hero (all authors do this—Parker is just a lot more blatant, and a lot more opportunistic, than most). I could still live with him, though, because some of the dialog, some of the locations, and some of the bit characters are still remarkably good. And he used to (not so much anymore) write absolutely riveting and very accurate fight scenes.

That’s mostly gone, and, as you might anticipate, his cranky-old-guy nature has come out more and more—it happens to us all. Unfortunately, a cornerstone of his Bahston-accented Grandpa Simpson is his really remarkable, and (considering his own academic background) unseemly, cheap shots at academics. I don’t know what the hell was done to him at Boston University, where he took a Ph.D. with a dissertation on Dashiell Hammett (what are you bitching about, Robert? You got to write a dissertation on precisely the author who you wanted to revive and cop from!), but, based on the absurd and petulant caricatures that riddle his books from the very first, he certainly seems to feel that every academic he ever met was a total pompous jackass. They’re there throughout his corpus: distant, arrogant, unkempt, “liberal,” petty, mundane, you name it. He only grants grudging absolution from this caricature to those occasional academics in his catalog to who he can carefully assign back-stories: as wrestlers, college football players, and so on.

Now, I’d guess that virtually every candidate who has gone through the process of a Ph.D. in the humanities or fine arts could share hair-raising stories about the delusional senior professors of their pained acquaintance, and God knows I’m no exception. One of the ways that people post-Ph.D. cope with the trauma of that experience is by telling and re-telling anecdotes of the horrible shit that was done to us. My beef with Parker’s characterizations (more accurately, caricatures) is that, by re-visiting and re- re-visiting them in book after book after book, and by rendering them in such absurdly stereotypical terms (the professor with the cat hair on his sweater or the grad student with frizzy hair and a sack-like natural-fibre dress), is that those caricatures don’t further either his story or the reader’s understanding of that story—in fact, they sound like the whining of a post-doc, overage in grade, who couldn’t get done with the document and is searching for excuses why. You want to say: “Robert, look—maybe your professors were Mean to you. Maybe some of them were space cadets or impractical. Maybe some of them even had cat hair on their sweaters or needed a haircut. But shit, Robert, you got your damned degree. You’ve sold hundreds of thousands of more than 50 titles which are all essentially variants on a single plot (Spenser meets person in distress, who is too poor or too stupid to recognize the merit of his services. Spenser boy-scouts his way into assisting anyway. Hawk and Vinnie and Chaco and Susan Silverman comment sardonically. Spenser has to do something he doesn’t want to do, and hopefully gets to hit someone. Conflict resolved; Spenser (Parker) once again told by rescued victim what a wonderfulMan’s Man he is). What the hell are you still bitching about?”

Professors mostly aren’t like that. They’re impractical, unaccountable, spoiled, self-loving, mundane and/or abstracted in equal balance. But they’re mostly not materialistic.

We traffic in ideas. And ideas—more than personalities or royalties or fudge or Budweiser caps or a trophy wife or a bully pulpit from which to stereotype the people who Hurt Your Feelings four decades ago—matter.

They matter.

Posted by

CJS

at

3:39 PM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: Workstation series

Friday, October 24, 2008

Folk music makes you tough

Several years ago, the Celtic Ensemble was playing a little festival in a town south of here: flatbed trucks for stages, little inadequate PA systems, punishing direct sun. The folks running the festival were really nice and very considerate, though they didn't really know what they were doing. And they had a tendency to book their friends, whose as musicians were pretty good visual artists: great at figuring out all the surrealist things they could do with visual presentation, but pretty shitty as musicians (there was some guy riding a sculpture, wearing a hazmat suit, made out of a bicycle which, when pedaled, would spin a horizontal disc to which were attached hanging beer bottles, on which he'd play percussion). But, the whole point of punk rock was that you didn't need to be a good musician in order to make music--in fact, worrying about being a good musician just got in the way.

Unlike those children, I remember the punk-rock movement and the sense of incredible liberation it bestowed when you put on the Pistols "God Save the Queen" at one of those 1978 dormitory disco parties and starting pogo'ing. And it was decades ago that I figured out that the defiant energy of punk-rock was already part of the world's folk traditions--but that you had to go out and find it.

In the event, at this little sun-drenched festival, the Art School kids were having fun being as outrageous as they thought they could get away with or looked cool, and that was all fine, until they started saying snarky things about me and my band. Now, in the age of Jon Stewart, Stephen Colbert, and Katherine Jean Lopez, irony is dead: it's so ubiquitous that it doesn't even have any meaning anymore. So I realized that the punk-rockers ahead of us were just trying to be "ironic" with no awareness that it might piss off somebody else.

But making fun of my guys, as any of them will tell you, is a quick trip to a long walk off a short pier with Dr Coyote. So when the Art School fucks had finally thrashed out their last tune, and the hazmat guy had disassembled his bicycle "sculpture," and the snarky lead singer had been introduced to me and had realized that, in addition to having 3 more degrees than he did, I was also a foot taller and about six times meaner, we got on stage for our first tune, and I said:

"You know what's the difference between 'folk music' and 'emo' music? Folk music is 'emo' that's grown up and moved out of its parents' basement."And we hit it.

Folk music isn't "twee," or "pretty," or "precious," or au courante, or bling, or any of that other temporary ephemeral bullshit. Folk music is tough, and it'll make you tough too.

I thought of that when I saw these videos from the legendary Oyster Band, now embarked on their Thirtieth anniversary tour:

Posted by

CJS

at

10:15 PM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: music, radical politics, vernacular culture

"The Office" (workstation series) 112 (satellite edition)

Live-blogging the conference. My paper's done and so I'm in a position to sit back and look at the event-as-event.

Live-blogging the conference. My paper's done and so I'm in a position to sit back and look at the event-as-event.

There's an ongoing quasi-serious conversation amongst academics about the actual cost - versus - benefit ratio of making attendance at and contributions to conferences significant markers of "research & creative activity": mostly because the actual benefit of a paper delivered to a dozen or two of one's colleagues, as opposed to the cost of time, absence, and environmental impact (helluva lot of academics take a helluva lot of plane trips), can seem pretty low. In an attempt to handle that, and to try to maximize the actual, tangible benefit of my attendance at conferences, I pretty much don't attend anything at which I'm not performing one or another kind of demonstrable tangible function: either chairing a panel or committee, delivering a paper or performance. There are still academics who seek or elicit funding from their universities simply to attend--to be present at--conferences, but those days are rapidly receding: as the number of people in the various professions expands, as the state-funding for universities recedes, the days when you get money to attend a conference simply for the 4 days' contact and "professional development" are also disappearing.

In part I'm OK with this: in an age of ever-reducing resources, academics should be thinking of maximizing return--in terms of both recruitment and their own professional development--and minimizing costs. And though I'm not one of those reaallllyy tiresome academics whose chief expertise seems to be jumping-upon and bruiting-about the latest political concerns and correctness--the ones who, in lieu of actually producing scholarship, harp on about how scholarship should be done differently--I do think it's legitimate for us to be thinking about ways to walk more lightly on the earth--in terms of both carbon footprint and general hot air. And there certainly are academics who seem to use the excuse of conference attendance (less often, of presentation) as a way to get out of town for a few days on somebody else's dime.

So there're pretty good arguments for avoiding those conferences in which you wind up presenting your research to a three-quarters-empty room, for an audience chiefly made up of other people presenting at the conference. It's not "public scholarship" if the general public beyond the co-attendees never sees or hears it. It's made more difficult in that, particularly if you are recruited for a panel at the meetings of a society whose profile you don't know (like the one I'm currently attending), there's no real way to read between the lines and assess in advance whether maybe this is going to be another of those light-attendance situations. And going, and only then finding out, feels like a pretty damned costly (for your funders) way of adding a couple of lines to your CV.

The other side of it, though, is that you also don't know when participating--by invitation--at one of these lightly-attended situations may have less insignificant or ephemeral long-term impacts: when you'll hear a great paper that really gets your own wheels turning and suggests new lines of research, or meet a scholar with whom you really think one of your students could do great graduate work, or meet someone else who might be able to offer you yourself additional scholarly opportunities.

This morning--for example--just prior to presenting a paper for a room of around 15 people, I got an invitation to collaborate in a much more long-term project, directly resulting from the kinds of six-degrees-of-separation connection which is one of the best aspects of conferencing. No knowing if this long-term project will pan out, but even the thinking-up of such projects is something that usually, directly, results from the person-to-person, face-to-face, blink-and-you'll-miss-it connections at conferences. You gotta show up to play.

And, of course, there's the pure-D self-discipline of having to complete a text, in order to present it at the conference, by a specific deadline. You can fudge this by selecting a topic that is very familiar to you, while unfamiliar to the audience, because then virtually anything you present is going to seem interesting or at least impregnable. This is a very easy strategy for musicians, for example, presenting at historical or literary conferences--those latter scholars are so gassed by hearing some pleasant sounds that they can be remarkably tolerant of slight content.

But, I'll also sometimes use a conference invitation to address a research/presentation topic which I've had in the back of my mind but haven't yet gotten around to. I've had the idea for this particular paper (on harmonic knowledge on a particular frontier in a particular period) in my head for at least 20 years, and it's only this year, with the impetus of this invitation, that I've finally got around to prioritizing the time to get the thing into draft.

So to this conference: it's primarily oriented toward historians and literary scholars of a particular period in Ireland. As such, they're not very knowledgeable about music--certainly not "literate" in the sense of knowing the notation or the technical terminology. On the negative side, that means one can get away with the kind of razzle-dazzle that musicians presenting for non-expert audiences learn how to exploit. On the plus side, it means that any presentation you make does have to be accessible and comprehensible to a non-specialist audience.

And this is a good thing--one of my pet peeves about academia is the degree to which we prioritize and reward very finely-argued and subtle arguments presented to one's peers, while de-emphasizing or failing to reward effective and accessible presentation to general audiences. This beefs me because I think the latter--speaking "outward" to a wider audience--is a lot more important than we give it credit for, while the former--speaking "inward" to our very small circle of co-expert peers--is less significant, in terms of overall positive impact, than we pretend it is. Moreover, speaking "outward" is a much closer parallel to the actual day job that we do,which is teaching. It's good to be a scholar, because it drives our own individual inspiration and continuing curiosity, but it's equally important to be an advocate for scholarship--to be able to frame, present, and argue the value of our insights to wider communities.

It's easy to respond with the accusation that such outreach runs the risk of dumbing-down the content of the scholarship, but I think that's an excuse, employed by scholars who don't really believe in the value of teaching and of being a public intellectual. We need to be scholars and teachers, researchers and advocates. Learning to succeed at both sides of these dyads--just like learning to teach undergraduates and graduates and continuing-education students--is an essential part of what the role of a public intellectual can be.

My revered dissertation adviser Peter Burkholder taught that "you should be able to articulate the point of your research in the scope of an article, a lecture, or a dissertation--or of a public talk, a note-card, or a single sentence." I've extended that aphorism, with my own students, in a parallel fashion: "you should be able to articulate the point and the relevance of your research to any audience: expert or non-expert, student or colleagues, undergrad or graduate, specialist or generalist, in any medium: scholarly or popular print, radio, television, lecture, conversation, or conference question-and-answer period." This is how you be a public intellectual; this is how you renew and revitalize the argument that historical, sociological, musicological, intellectual expertise and insight have something to say in a changing public world.

Yet, it is also true that the best critic of one's work is not oneself. I may think that this paper, which--though I've been thinking about how I would write such an item for at least 20 years, as I say--was written within the last 2 weeks, is a relatively straightforward, relatively small-scale idea presented with some razzle-dazzle so as to provide a nice bit of relief for the history/literary people.

But what I think about the paper is unlikely to provide an accurate assessment of either the depth of content or of its potential value or reward for others. One of the ways we can psych ourselves out regarding the quality of our own scholarship is to lose track of the degree of familiarity versus unfamiliarity, "the obvious" versus "the insightful" in a topic we've thought about for a long time. As I tell my writing students, there is no way that we as individual scholars, thinking sometimes for years about a topic, can assess the "newness" or new insights in our treatment. If you've researched and thought about a topic for months, or years, or decades, you are by definition uniquely equipped to think about and present that information--but by the same token you can't assess its impact upon or novelty for someone else.

So we, once again, separate out the roles of author versus editor, presenter versus recipient. We have to do this when we're writing--the quickest recipe for writer's block is to conflate the activities of writing and editing together: to start editing and re-writing a text, paragraph, or line before we've even finished creating it in the first place. This is also why every writer, no matter how skilled, needs external editors. The very expertise we develop in analyzing a problem and conveying our insights by definition un-equips us to assess the suitability, tone, accessibility, and so on of that presentation for an audience or reader.

This is also why giving a paper at a conference--even something that seems relatively "slight", for a sparse and/or easily-dazzled audience--is almost always a valuable exercise for a writer. It may be sort-of pointless in terms of career development, but it's almost always useful in terms of intellectual development. Because it lets the entire audience respond as both auditor and test-case, it's an incredibly constructive exercise for an author. Things you think are obvious are heard as abstruse or challenging; things you think are slight or prone to razzle-dazzle are heard as brilliant and exciting. It's like a test-screening for an audience who actually care about and have some insight into your treatment.

It's a drag, and costly, and boring, and time-consuming, and it ain't that good for the planet--but more often than not, it's also worth doing.

Below the jump: the view at the end of the day:

Posted by

CJS

at

8:26 PM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: Workstation series

Wazzzuuuppp??????

Cross-posted from Radical Musicology:

Posted by

CJS

at

8:25 PM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: radical politics

Thursday, October 23, 2008

He's a teacher, right?

Obama on the decision to "go big" in the post-Jeremiah Wright "scandal" about race--instead of "small":

My gut was telling me that this was a teachable moment and that if I tried to do the usual political damage control instead of talking to the American people like an adult -- like they were adults and could understand the complexities of race that I would be not only doing damage to the campaign but missing an important opportunity for leadership.I can think of a few other teachers, and community organizers, who'd I want as my president, too.

Posted by

CJS

at

6:21 PM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: radical politics

Wednesday, October 22, 2008

Tuesday, October 21, 2008

Day 35 (Round II) "In the trenches" (short-week edition)

Short-week, short posts this week as a result. Heading on up out of here in around 48 hours for a 3-leg/dog-leg trip to two different conferences. Anymore, it's more efficient (though also more wearing) for me to try to double-up or otherwise maximize what happens on the trips out of town.

Short-week, short posts this week as a result. Heading on up out of here in around 48 hours for a 3-leg/dog-leg trip to two different conferences. Anymore, it's more efficient (though also more wearing) for me to try to double-up or otherwise maximize what happens on the trips out of town.

In light of that time-jam, here's a short cut 'n' paste from a response to a new student who asked about my own musical and instrumental background:

Grew up as a rock/blues (acoustic & electric) player. Did a master's degree in jazz guitar with David Baker and a lot of years playing bebop. During graduate school developed secondary specializations in early music (lute, saz, oud, gittern, hand drums) and in South/West African (amadinda and akadinda xylophones, balafon, kamelengoni), North African (oud, dumbek), and Afro-Cuban (tres) musics. Been playing Irish traditional music (tenor banjo, bouzouki, open-tuned guitar, bodhran) since around 1974. In the last two years have picked up Appalachian old-time music (clawhammer banjo). Currently mostly play bouzouki & tenor guitar (Irish music), National steel guitar, clawhammer banjo, and mandolin (pre-WWII blues).

Below the jump: seasons changing on the South Plains:

Posted by

CJS

at

8:41 AM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: music, Trenches series

Monday, October 20, 2008

Blogathon for Arts Education

Culture Bully (Twin Cities) running a 60-hour blogathon with area musicians about how music & arts education changed their lives.

Posted by

CJS

at

10:41 PM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: music, vernacular culture

Day 34 (Round II) "In the trenches" (lights-out edition)

Week 09: lot going on. Extra-short (or extra-long) week for me, as I'm double-dipping on a conference weekend: one in St Louis (panel on 16th century Ireland; my paper is "Gaelic and Continental Interaction on Europe's Harmonic Frontier") and one in Connecticut (panel at the Ethnomusicology meetings; my paper is on Afro-Celtic musical interaction in the minstrelsy project). Both papers are done--the latter I could basically improvise--and I like hanging with various professional peeps.

Week 09: lot going on. Extra-short (or extra-long) week for me, as I'm double-dipping on a conference weekend: one in St Louis (panel on 16th century Ireland; my paper is "Gaelic and Continental Interaction on Europe's Harmonic Frontier") and one in Connecticut (panel at the Ethnomusicology meetings; my paper is on Afro-Celtic musical interaction in the minstrelsy project). Both papers are done--the latter I could basically improvise--and I like hanging with various professional peeps.

But I still wish I didn't have to go. At this stage of my life, I would substantially rather have the extra time at home, and avoid the cost- and time-sink that is travel. Though lots of colleagues like the conferencing because it gets them out of their local environs and lets them interact with professional peers, and I like that too, at this point I need the time way more than I need another line-item in my CV. I recognize that this is a good problem to have--lots of people are in the position of still having to scuffle hard to locate conferencing opportunities, and at a point in their lives when they usually have to pay for the damned things out of their own pockets. It's a frustrating irony that, as you get a little more advanced in this profession, the opportunities to present conference papers increase in inverse proportion to the amount that you need them for your CV, and the degree to which you have to pay your own way (as opposed to having your employer foot the bill) decreases in inverse proportion to the degree to which you could. The younger you are in this profession, the more you need the conferencing opportunities and the harder they are to come by. The older you are in this profession, the more you can afford to pay your own way, and the less you have to.

I am sufficiently conscious of this that, when the most recent round of travel-money requests went in, I told the Boss: "look, if as always you don't have enough money to fund everybody, for cryin' out loud give the most of it to my junior colleagues--they need the CV items and they lack the money a lot more than I do." Not that he can necessarily do that--and I recognize that my presence out there presenting and chairing at the national conferences is an important part of our recruitment--but I still wish there were ways to invert those equations such that my more junior colleagues got more help more readily.

Below the jump:

Damn. Just damn. Lights out on my boys.

Posted by

CJS

at

8:47 AM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: Trenches series

Friday, October 17, 2008

Day 33 (Round II) "In the trenches" (icy mofo edition)

Yes: Barack Obama is one icy mofo.

Yes: Barack Obama is one icy mofo.

Beyond that: EOB, 8th week of school. We're now more than 1/2 way through the semester. First exams are done, first hurdles of student openness and responsibility are past, mid-semester grades go live over the weekend, because there is no real point in giving freshmen additional time to freak out and scream for mercy in a misguided attempt to pull a grade change--better that they encounter those grades after the window for changing them is past. As a colleague says, very wisely, "They need time to calm the hell down." Many kids, encountering a grade they don't like or which they know won't fly with Mom 'n' Dad, will fire off a scattershot pleading email, not necessarily because they think it will have good odds of success, but simply because it is so easy, in their on-demand mindset, to throw the plea against the wall on the off chance that it'll stick. It takes them so little effort that they'll do it just to play the odds.

Which is precisely why we ignore such "tear-stained emails" (Dharmonia's construction) until the cutoff time is past. In the unlikely event that there has been an error, or even less likely that we will grant a grade change due to extenuating circumstances of which we've previously been unaware, we can always do that after the cutoff date. And, in the much commoner instances of grade-change-requests which have absolutely no justification in any objective factual world, ignoring until past-deadline is a good way to just make the little bastards, as my colleague said, calm the hell down. If the grade-change request doesn't stick against the wall, they'll mostly just throw up their hands and belatedly accept the grade earned, as they shouldd have done earlier.

On the other hand, it seems like a good bunch this year: not too whiny, reasonably good attendance, reasonable good attention, pretty responsive to the jokes 'n' japes. Every year's intake of new freshmen is different and there's no real predicting in advance, but I think what we're seeing here is an eventual manifestation of our enhanced admissions criteria. That is not to say that kids with higher academic achievement are automatically going to be either (a) more talented or (b) more mature/focused in their work--that's putting the cart before the horse. To stretch the metaphor: the kids with higher academic achievement have already--before we get 'em--learned that a focused, mature, and disciplined attitude about work in turn leads to better results (and a better ability to take advantage of whatever talent the universe has given you). Kids with greater academic problems, problems already manifesting in secondary school, are slightly more likely not to have yet learned the self-discipline and work-ethic stuff. As I've said before, music undergrads tend to be way more conscientious and self-disciplined, simply because they've had to learn to be that way in order to learn to cut it on their instruments. Unfortunately, not all of those latter have learned to transfer the lesson from study of an instrument to academic study. We'll do the remediation, but the less remediation we have to do--and the less we have to fight our way through their uninformed skepticism about whether they need to accomplish what we set forth--the easier it is for everybody to progress effectively together.

This year's seems like a pretty good bunch.

Below the jump: the "Santa Ana" tomatoes that the proverbial Old Guy at the Garden Center said were "the on'y kahn'a termaters that'll grow in Wes' Texis." By God he was right, too: after three years of growing healthy vines but no fruits in the raised beds I built for Dharmonia, these are wonderful: thick-skinned, but with wonderful juicy and chewy innards: absolutely great for cooking, canning, or sauces. Below that, a counter-ful of veggies that I'll turn into various circum-Mediterranean eats: tiny pickling cucumbers, tossed in salt so as to draw out moisture and in turn make them receptive to soaking up the brine for refrigerator pickles; lemons that, with garlic and basil, will go into the Provencal cannelini (white beans)--lemon, garlic, basil, and pepper are the essential combination of flavors for southern French and some central Italian cuisines; broccoli to be sauteed in olive oil in which the chopped garlic on the right has previously been browned; the aforementioned tomatoes (great for sauce, but also--when still warm from the vine--great just slicked and drizzled with a little olive oil and salt); whole-wheat pasta to be dressed with a little garlic, oil, and grated romano cheese.

Good peasant food: cheap, healthy, low trans-fats, mostly-dairy-free. And no animals had to die for it.

All we can do is make the most/best of our time here.

Daniel certainly did.

Posted by

CJS

at

12:51 PM

2

comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: food, peasant food, Trenches series

Talent is temporary...tough is permanent

Red Sox 8, Rays 7: Down by 7-0, Red Sox Force a Game 6

Seemingly dead, the Red Sox unfurled a miraculous rally in the last three innings of Game 5 of the American League Championship Series on Thursday.Yeah baby. Talent is temporary...but tough is permanent.

Posted by

CJS

at

11:37 AM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: vernacular culture

Thursday, October 16, 2008

Quick hit: graffiti verite

The following exchange on a men's-room wall in the Music building is a little too accurate to feel irked about...

Writer #1: "Dr Coyote's class sux balls!"Well, at least they know my modus operandi.

Writer #2: "What is your evidence for that? Cite specific SHMRG characteristics."

Critical writing is critical writing, no matter the medium.

Posted by

CJS

at

11:28 AM

1 comments

![]()

![]()

Wednesday, October 15, 2008

Apropos nothing I can reference...

...lemme just say I love my guys.

Posted by

CJS

at

9:03 PM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: Education, Trenches series

Day 32 (Round II) "In the trenches" (telegraphic cuisine edition)

Just ain't no time for considered prose today--too many events, too many people, too many deadlines to meet. So, in lieu of said prose--and because I'm trying to keep my mind off Round III and Final of the Smackdown going on over on the network channels, here's some good cheap peasant food:

Just ain't no time for considered prose today--too many events, too many people, too many deadlines to meet. So, in lieu of said prose--and because I'm trying to keep my mind off Round III and Final of the Smackdown going on over on the network channels, here's some good cheap peasant food:

Dr Coyote's Silk Road Special (pilau for poor folks):

Cook one cup red or green lentils (red are prettier) in about 4 cups water, at a light boil, for around forty minutes; when cooked until al dente, drain but reserve the water.

Cook one cup of basmati rice in at least a thumbnail's depth of water (see prior treatments); once boiling, reduce to simmer, cover, and leave it alone.

In a decent-sized skillet, cook approx 4 cloves chopped garlic in 1 tablespoon olive or sesame oil until golden brown; add 1 cup chopped onion and continue to saute, until lightly browned. Add a solid teaspoon of turmeric and same of cumin to garlic/onion mixture; saute on slightly-reduced heat until spices are dissolved into and coat the vegetables.

Add the lentils to the garlic/onion/spices, plus a splash (about 1/3 cup) of the cooking liquid. Stir over moderate heat for a minute or two, until all ingredients are mixed, and the liquid is mostly reduced.

Add the rice to the lentil/garlic/onion mixture and stir over low heat until mixed. Add black pepper, and a dash of salt (to taste). Garnish with grated almond or chopped pine-nuts. Serve with a green salad and warmed pita bread. And a nice rough red wine is never unwelcome.

Should feed at least 4 for one meal--or two, with leftovers for next day (to prepare as leftovers, stir/warm on the stove in a dry skillet).

Posted by

CJS

at

7:24 PM

2

comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: peasant food, vernacular culturem

Tuesday, October 14, 2008

Day 31 (Round II) "In the trenches" ("Soft Day" edition)

Same-same. Beautiful rainy day full of shivery little Texans going past the coffeeshop windows--what in Ireland would be called a "soft" day: essentially any day in which the rain doesn't have a cold wind behind it. Texans definitely don't experience it that way, though ("Ah'm saow kaold! Ain't chew kaold?!?"). Ah well; this would be a good day to sit in a pub and play tunes. More preferably There than Here.

Same-same. Beautiful rainy day full of shivery little Texans going past the coffeeshop windows--what in Ireland would be called a "soft" day: essentially any day in which the rain doesn't have a cold wind behind it. Texans definitely don't experience it that way, though ("Ah'm saow kaold! Ain't chew kaold?!?"). Ah well; this would be a good day to sit in a pub and play tunes. More preferably There than Here.

Moving into 8th week now. Kids are pretty well-locked in: Dharmonia's take on it is that they're exhausted, but myself I think they get a lot more worn-out in the spring semester, with all the distractions and interruptions of tours, TMEA, and spring break. In the fall semester, 2nd week of October is when they're pretty much over the acclimatization of realizing they're in college, first round of exams is past, and they're settled in/buckled down.

I also think this is the period when they begin to trust the experience, and each other, and even me. Nobody's died or flunked-out in the wake of the first exam, I haven't humiliated or otherwise abused anybody in class, and, most crucially, I've put them through the first round of progress reports: an opportunity for the student--in class, over email, or by anonymous note--to convey to me what is or isn't working. The generic way of handling state-mandated evaluations is to do them right at the end of the semester: distribute the scan-trons and the comments sheets, leave the room, have a proctor/monitor/graduate student pick them up and turn in directly (as confidential information) to the departmental staff.

While the premise behind this--that students' impressions should be considered in any assessment of teaching effectiveness--is sound, the reality of the execution is flawed at all kinds of levels: there are the legion opportunities for abuse and irresponsibility on the part of vindictive little criminals who just want to tank a disliked professor's percentage averages, or say mean and hurtful things (this is why the strategy I've blogged about before, of having a trusted colleague read and digest the evaluations, is a good one).

But there is a larger, more significant reason to re-think the process, and the purpose, of evaluations: the students supplying evaluations--responses to which should presumably include at least the possibility of course redesign or re-thinking--in the 16th week of the semester do not have the opportunity to benefit from any such redesign. They're essentially being asked to improve, for future generations of students, an experience which they themselves are just ending.

This seems counter-productive--or at least incomplete. Surely students currently enrolled in a course, if they are to provide evaluative comments and feedback, should also have at least the faint chance of benefiting from that feedback? If evaluations happen only at the end of the semester, this is impossible; and, moreover, the students know this is impossible. And so the investment by the good and conscientious students in the end-of-semester evaluations is low and their contribution to same small, which leaves more space for the spiteful and vindictive criminals to hold for (though, thankfully, the worst of those latter have tended to drop the course, or simply stop attending, by Week 15).

Much better, it seems to me, to open up the process of back-and-forth dialog much earlier in the semester: ideally, after the first acclimatization has occurred, after the first tools of assessment (especially exams), but before mid-semester grades we're required to issue to freshmen and athletes--an excellent practice likewise aimed to catching a failing kid while there is still time to remediate. Nothing focuses an 18-year-old's mind like Mom 'n' Dad yelling over the phone "How the hell did you manage to get a C- in only 8 weeks of class?!? Do you want to come back, live at home, and attend a community college?!?"

But I need to catch them, for evaluation purposes, before that mid-semester shock of cold water hits. Not so much because they can target me: I'm tenured, and don't have to subscribe to the "bring brownies andd avoid assignments on evaluation days".

But more because I want to catch them when their minds are relatively clear: when they're relatively able to focus, and think clearly, and least subjectively, about the process and their own responsibility within that process. So along about the 7th or so week of classes, I'll put this up on the Powerpoint screen: And I'll say, "Let's have a conversation about this. What's working for you? What's not? We still have time to make changes that will help you excel; how can we all take responsibility for doing so?" I'll tell them they can respond to me right then, or over email if they're too shy for face-to-face, or by anonymous note in my mailbox if they would otherwise feel unsafe.

And I'll say, "Let's have a conversation about this. What's working for you? What's not? We still have time to make changes that will help you excel; how can we all take responsibility for doing so?" I'll tell them they can respond to me right then, or over email if they're too shy for face-to-face, or by anonymous note in my mailbox if they would otherwise feel unsafe.

The goal is two-fold; its side-benefits are multiple. Goal 1 is simply to convey that they are entitled to provide feedback about what is working for them, and that such feedback is valued and attended. Goal 2 is to convey that dialog is an essential part of an adult situation: that both sides have rights as well as responsibilities, and that some of these are negotiable, but they can only be negotiated if both sides take responsibility for participating in the conversation (directly, via email, or anonymously--that part doesn't matter).

The side-benefits are even more profound, I think. First, it simply demonstrates that the faculty member in charge has both the confidence and the moral clarity to open up the possibility of critique: that the authority in the classroom derives not from the club/threat of the grade. Such power-imbalance is implicit in every classroom; "if I criticize the teacher, will I be victimized with a bad grade?" Anything that explicitly addresses that, that conveys "you are entitled--and safe--to express a critical opinion," empowers not only the student but also the teacher, and makes it clear that the latter's authority derives from expertise and skills to be conveyed--not from threat.

Second, it permanently and positively changes the nature of the in-class dialog. If the teacher opens up the possibility of student critique, and has honestly created a sufficiently "safe" environment that any given student offers such a critique, and the teacher is seen to respond fairly, thoughtfully, and openly, then all other students present have had modeled for them a kind of safe, mutually respectful conversation between two valued participants. This makes all other classroom conversations, of all sorts, much more open and egalitarian.

Third, and perhaps most lastingly, it's another important stage in a freshman's growing-up-and-taking-responsibility-for-your-own-damned-education maturation process. If the teacher provides you a safe, open, responsive, respectful arena (in-class, via email, or anonymous) in which to express your critiques or concerns, then you as the student must take responsibility for expressing that feedback. If the student does not, then s/he really has no cause to complain, right?

Of course, some of the lazy and immature ones will neither respond nor refrain from complaint: these are the ones who love to sit on the front steps of the music building, smoking cigarettes, and talking about "how much this place sucks." But, even if they continue in their taking-no-responsibility arrested-adolescence high-school-esque behavior, they've had modeled for them a kind of dialog that asks them to grow up. And the vast majority of them will rise to this opportunity, will grow up and begin to learn what it means to be an adult, taking responsibility and owning your education, human person.

One of my admired colleagues, now moved on to other pastures, put it very well, when he said, "I've come to think of my job as being about more than music. It's about using music to teach young people how to be human beings." Prior commenters, when I've cited this anecdote in the past, have taken the very politically-correct stance of "Oh, I would never presume in the classroom that I could teach someone how to be a human being...how very domineering and patriarchal of you!"

But I come from a much older school. Much older.

I come from the place where it was the sacred duty of the elders of the tribe to teach the younger ones how to survive. Because if the elders didn't--if they shirked their duty, which included not only passing-along data and knowledge, but also modeling a way to be a functional adult human--then the tribe would cease to exist. Part of that legacy has to be, not just knowledge and data, but also being an admirable and emulatable role model yourself.

Damned right I'm going to show a young person how to be a Human Being. That's my job and my heritage.

Posted by

CJS

at

8:43 AM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: Trenches series, vernacular culture

Monday, October 13, 2008

Day 30 (Round II) "In the trenches" (Fog and Pomposity edition)

Sometimes you put in the headphones just to block out the crap that flows into your sonic space. Sometimes it's two 19-year-old bottle-blonds in sweats and Ugg boots (but with their makeup perfect) swilling down the large Starbucks Mocha Frapuccino's paid for with a credit card that's billed to Daddy while they talk about which guy who has asked them out is likely to have the biggest allowance from home--and thus be the best investment. Sometimes it's the hardy-har-har "funnymen" on the local Fox Talk radio station the sum total of whose attainment is the morning 6am-10am "drive time" Rants and Scores segment--and at which even that they're failing.

Sometimes you put in the headphones just to block out the crap that flows into your sonic space. Sometimes it's two 19-year-old bottle-blonds in sweats and Ugg boots (but with their makeup perfect) swilling down the large Starbucks Mocha Frapuccino's paid for with a credit card that's billed to Daddy while they talk about which guy who has asked them out is likely to have the biggest allowance from home--and thus be the best investment. Sometimes it's the hardy-har-har "funnymen" on the local Fox Talk radio station the sum total of whose attainment is the morning 6am-10am "drive time" Rants and Scores segment--and at which even that they're failing.

But sometimes it's my goddamned colleagues and peers--tenured faculty members addicted to the First Person Pronoun, holding forth in performance for their table-mates (and anybody else within a 20-yard radius) and practicing the worst kind of identity politics.

One of the terrible outgrowths of the '60s--and something for which I and people like me are partially culpable--was the mutation of empowerment. I am not a '60s revanchist--I still believe that was, with the periods 1770-92 (Boston Massacre to the Constitution) and 1890-1919 (Populism to the Palmer Raids), one of the most important and profoundly net-positive periods ever in American history. Taking off from the socio-political opportunities offered by the (productive) chaos of post-WWII, and the determination of entire minorities (blacks, Latinos, women, gays & lesbians) not to hold still for the repressive shit that had obtained in America pre-1939, the underground '50s (especially jazz and the Beats) and the aboveground '60s (especially Civil Rights, Vietnam resistance, and popular music) were a period of enormous and positive social change in this country--and a period that repressive assholes like Dick Cheney have been trying to roll back ever since (Cheney got 5 deferments from Vietnam, in part by narking-out numerous anti-war groups in Ann Arbor). The Civil Rights movements of the '60s led directly to Gay and Women's Rights and to the environmental movement. And those were/are Good Things.

But, the regression of the 1970s "Me Decade" and the long narcotized sleep of the 1980s Reaganesque "Greed is Good" era also did bad things to the social justice and freedom-of-speech ethos. It meant that at least in part people concluded they could accrue political power, in the post-60s era, by practicing identity politics and the politics of victimhood; e.g., "I am, or have been, or might have been, or can re-calibrate my public persona so as to seem, a member of some oppressed minority...and therefore I'm entitled to special consideration." Of course this strategy is practiced most commonly of all by those who, in the '70s and '80s, felt their entitlements slipping away: chiefly straight white men.

But in the last 20 years, it's become increasingly prevalent throughout all streams of our political discourse and in practice by all different kinds of social groups, including both those groups who have absolutely no fucking business claiming oppression (that would be the aforementioned straight white men Like Me) but also by other groups who have been oppressed but whose individual claimants do not necessarily any longer have much business making the claim either. I'm sorry--all people, even the aforementioned, have had hard times and been mistreated: even straight white men probably had some measure of shitty demeaning experiences, and poverty, just fighting their way through graduate school, so all people have endured suffering and mistreatment.

And if you're a tenured full professor on a university faculty with a job teaching the precise field of Identity Politics which you yourself subscribe to--the specific oppressed minority which you both embody and pontificate upon--could you please recognize that you're actually a pretty damned privileged person, not matter what/which experiences of Oppression you--or maybe just your predecessors in the minority--might have endured? Identity politics is tired, and tiring, and in and of itself, it is not scholarship. Just saying "I'm going to tell all you students how to think how this literary or historiographic problem because I am a member of the oppressed minority whose experiences are detailed in this problem" is not pedagogy--it's polemic. But because it's a university setting, and you're the tenured full professor of X Studies, and you're mostly dealing with 19-year-olds who are open and receptive to modeling themselves upon you, it is goddamned easy to become very enamored of your own voice. Call it the Ward Churchill Syndrome.

The people who came out of the Cultural wars of the '60s and early '70s sanest, least egocentric, and most self-aware were those who had some kind of spiritual/sanity practice in place (in my own tradition, that would be the various Tibetan and Japanese Buddhist groups, but I'd include in the same groups the various Catholic Action and other socially-engaged movements--in fact, some of the sanest post-60s people I ever met were the back-to-the-land hippie pagans in southern Indiana, whose leader said to me once "I've never understood how somebody could call themselves a 'pagan' if they'd never even planted a garden"). Absent some kind of self-reflective regular practice--and, I would argue, a wise teacher who will regularly kick your ass to examine your own failings as well as pointing out those of the world--it is just too damned easy to presume that your expertise in a single narrow area of scholarship, or hell, even your own identity politics in place of scholarship, entitle you to sit in a coffee shop and hold forth at great length and loud volume.

My old brother-in-music-and-combat Quantzalcoatl (now happily returned to the arena--welcome back, mijo!) calls it the "fog and pomposity" index; easily the best and most apposite description of professors' tendency to mistake their own opinions, or identity politics, as received truth.

Why is it, so fucking often, that the most articulate advocates for social justice and positive change are also such personally self-aggrandizing egocentric blowhards? Why can't they just do the fucking work and shut up about themselves? Why are so goddamned many professors such ubiquitous (and remarkably un-self-aware) practitioners of Fog and Pomposity?

Why am I?

----------------

Now playing: Dick Gaughan - Stand Up For Judas

via FoxyTunes

Posted by

CJS

at

8:48 AM

1 comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: Trenches series

Thursday, October 09, 2008

Day 28 (Round II) "In the trenches" (On the Road Again edition)

Here we go round again...

Here we go round again...

Off up outta here, at least for 72 hours. Editorial meeting in points back east: a day of travel, a day of meetings, another day of travel. Fortunately the course calendar and the competence of the teaching assistants meant no class-time need be lost--the worst thing about canceling an undergraduate class is not even the lost working-together time, it's the loss of continuity. Undergrads find it hard enough to concentrate when they have a class meeting every other day: give them five days off between meetings and they're forget that they're even in college, much less in this class. TA, with a couple of colleagues' backup, will run undergrad class Friday AM.

Editorial meeting is for this team-authored music appreciation textbook. I don't do particularly well with editorial third-parties at the best of times--though I love being edited by individuals whose competence I trust--and I really dislike the indirection and subjectivity that anonymous outside reviewers can bring to the assessment of a scholarly text. It's kind of like tenure votes: anonymity, no taking-responsibility for one's comments, and an entirely unreviewed opportunity to grind one's own particular perspectival axes. I reckon I'm a little too arrogant--and too scarred by years of graduate-school abuse--to trust the motives of some anonymous jamoke who isn't going to have to answer for his language.

This is a little different: because it's team-taught, and because it's a textbook, not a piece of interpretive scholarship, the process of along-the-way assessment is structured differently in order to address current concerns. Instead of sniping comments from anonymous reviewers who obviously are miffed that you either don't share their opinions or haven't read their idiosyncratic take on whatever topic, you get feedback from potential users of the textbook, responding to a fairly clear and concrete set of assessment questions aiming at the salability of the final publication.

And you know what? That's a better, more apposite, and damned sure more accountable assessment than whether or not a piece of interpretive writing concurs or disputes with some anonymous reviewer's prejudices du jour. So I'm not sorry to have the feedback: in a piece of contract writing, I accept that the parties making the final judgement about what's working or isn't have to be the people who are going to sell and/or use it.

On the other hand: this morning (travel day) is the first opportunity I've had to open the dozen-or-so documents containing reviewer comments. Not liking to read criticism of my writing, and not having time until today to respond in any way to any criticism, I just figured I'd save myself the stress (my stress level is quite high enough as it is, thanks).

So when I did finally get time to open the documents, I ran a quick multi-file word search for, first, the name of the genre I'm writing on, and, second, my own surname. Out of fifteen reviewers' multi-page documents, you know how many citations I found for either genre or surname?

One.

One sentence of direct (albeit useful) feedback speaking specifically to my chunk of writing.

I can't help but feel that 3 days of my life would be better spent writing, than sitting in a conference room in NYC listening to other parties talk about other chunks over which I have no control.

Sigh.

Posted by

CJS

at

2:49 PM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: Trenches series

Wednesday, October 08, 2008

New blog. Warning: invective advisory

Folks:

Have created a new blog: Radical Musicology.

I know and am tremendously grateful that some of my own students read Coyotebanjo, but I also know that many of them see political and social-justice issues differently than do I.

I'm intending to post the most radical political material over there, no longer over here, so that those students who are made uncomfortable by invective and spleen can focus on the topics at Coyotebanjo. I want my people to feel happy and comfortable about visiting for the pedagogy & scholarship topics, even if they prefer to avoid the more inflammatory stuff.

This will be a comparatively infective and spleen-free zone. On the other hand, if you like those kinds of posts, feel free to check out the new baby.

Posted by

CJS

at

5:59 PM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: radical politics

Tuesday, October 07, 2008

Day 27 (Round II) "In the trenches" (breathing-space edition)

As in, 72 hours of breathing-space, anyway: medieval band concert dropped Saturday night,* Sunday night was first practical/hands-on rehearsal of Celtic Ensemble's Welsh "hard" repertoire, last night was "First Monday" Irish ceili dance, and I don't have to go out of town 'til Thursday.

As in, 72 hours of breathing-space, anyway: medieval band concert dropped Saturday night,* Sunday night was first practical/hands-on rehearsal of Celtic Ensemble's Welsh "hard" repertoire, last night was "First Monday" Irish ceili dance, and I don't have to go out of town 'til Thursday.

Best part? It's now October, and I no longer have to give up 8 hours once a week to a grand jury. Learned a lot, but mostly about my grand jury colleagues, rather than the local level/incidence of crime--for a city of 202,000, this is a relatively/remarkably safe place to live. Takeaway points?

(1) Prohibition doesn't work, except to enrich (a) anybody who owns stock in a legal alternative (both booze and pharmaceutical industries come to mind--I don't see Cindy McCain going to jail, do you?) and (b) anybody who sees drugs as an entry-level entrepreneurial opportunity--viz The Wire's brutal evisceration of Republican "Just Say No/Three Strikes and You're Out" jurisprudence. You want to end the cheap, dangerous, bathtub drugs like crack and meth? Make cheap alternatives like methadone legal, require prescriptions, tax the fuck out of them, and invest in drug-treatment instead of incarceration. Both your crime syndicate activity (from suppliers) and your property crime (from users) will plummet.

(2) Enforce restrictions upon alcohol sale, use, and abuse much more stringently. Any kid busted for underage drinking should lose their license for a year--let 'em ride the bus or their fucking bicycles, and they should be on probation that whole time. Three quarters of the violence we saw was in either domestic or barroom contexts. Of course, that would mean that when Tyler or Melanie gets busted for DWI in their Grand Cherokee or GMC Titan, they should fucking go to jail for booking, and then should be assessed around 5 grand in fines--hit Mommy and Daddy in the pocketbook--and take their fucking cars away.

(3) Domestic violence needs mediation. That means that any time a family member is assaulted by another, the assailant needs to go to jail, regardless of whether the victim wishes to pursue charges--or even more, if they don't want to--and the victim needs mandatory counseling regarding alternatives, and needs the financial assistance to take those alternatives.

(4) Traditional electronic and print media reporting about local crime is almost always false in its impact if not its intent. Most crime in this city is not violent: it is petty property crime driven by addiction. TV and the (abysmal) local rag invert this, only ever reporting crime on the infrequent occasions when it is violent.

(5) Gun violence is almost always domestic. Trigger locks, background checks, and waiting periods should be mandatory, any loopholes should be closed, and any gun dealer (or private individual) or subverts them should go to jail.

(6) After-school programs, child protective services, and education/prevention initiatives should be funded to the max. We need a shift in public perception regarding punishment versus prevention/education comparable to the shift that Mothers Against Drunk Driving managed vis-a-vis driving while impaired. Until local and federal government commit the resources to prevention/education that they currently dedicate to incarceration/punishment, these cycles of abuse, violence, and crime will continue. Which I am cynical enough to believe Republican government prefers, because it keeps the electorate scared, passive, and amenable to whatever fascist posse comitatus bullshit they decide they want to pull.

Finally:

Good Citizens have no idea why/where crime happens, or how many of their Good Neighbors participate in it, or how much it's driven by economic factors (of course poor folks commit more crimes--they don't have any fucking money): rich folks' vices are usually not treated as felonies, and on the infrequent occasions when they are, the rich folks have the money to lawyer-up and get out of serving penalties. Poor people are intentionally prevented from having the same legal options.

We need a new goddamned vision in this country.

* I'll have more to say on this in a future post, but let's just say there that thank God, we didn't suck wind in front of Dharmonia's and my colleagues--18 years of playing together, even if it's now much more infrequent, and we still have that telepathy; rusty, and some noise on the channel, but it's still there. Afterwards, at our traditional post-concert booze-and-talk session (that's what medieval musicians do after the show: they get drunk and talk philosophy), I made what's become my own traditional toast, to the man who was our Great Teacher.

Thank you, Tom.

Posted by

CJS

at

9:29 AM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: Trenches series, Workstation series

Monday, October 06, 2008

Day 26 (Round II) "In the trenches" (brevity edition)

You know what is the best part of my job?

Happy kids.

You know what's the hardest part of my job?

Suffering kids.

Posted by

CJS

at

1:41 PM

1 comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: Education, Trenches series

Friday, October 03, 2008

Thursday, October 02, 2008

Swamped

...is what I am. Medieval band concert in just about 48 hours, 2 papers to deliver (on the same weekend! in the same weekend!) in two weeks from now, classes to keep up with, computer hassles to solve.

No time today--and I plan to be playing music tonight when Caribou Barbie attempts to prove that know-nothing intolerance is still a magic-bullet for a party bereft of ideas or credibility.

Posted by

CJS

at

4:37 PM

1 comments

![]()

![]()

Wednesday, October 01, 2008

Day 25 (Round II) "In the trenches" (investing my life edition)

October 1 (yes, it's Oktoberfest Month but that's the half of my cultural heritage that I am not particularly committed to); officially entered mid-semester now. Many classes across campus have entered post-Exam-I mode, and the kids have entered the concomitant shell-shock when they realized that yes, partying for a month instead of going to September classes actually will show up on your GPA, and that Mom 'n' Dad will (belatedly) drop the hammer when it's they themselves, rather than school districts and property taxes, are paying the costs for Junior's infantile alcohol-fueled effort-intolerant lifestyle. So there's a lot of whiny cell-phone conversations in the Starbuck's line about "but I really tried hard for this exam" (unspoken subtext: "I didn't try hard before the exam, and I'm personally offended that having 'tried' doesn't count the same as having 'succeeded') and a lot of kids walking around pale and resentful.

October 1 (yes, it's Oktoberfest Month but that's the half of my cultural heritage that I am not particularly committed to); officially entered mid-semester now. Many classes across campus have entered post-Exam-I mode, and the kids have entered the concomitant shell-shock when they realized that yes, partying for a month instead of going to September classes actually will show up on your GPA, and that Mom 'n' Dad will (belatedly) drop the hammer when it's they themselves, rather than school districts and property taxes, are paying the costs for Junior's infantile alcohol-fueled effort-intolerant lifestyle. So there's a lot of whiny cell-phone conversations in the Starbuck's line about "but I really tried hard for this exam" (unspoken subtext: "I didn't try hard before the exam, and I'm personally offended that having 'tried' doesn't count the same as having 'succeeded') and a lot of kids walking around pale and resentful.